CREMIT, Research Centre on Media, Information and Technology Education, Department of Education

Catholic University of Milan, Senior Lecturer

Email: alessandra.carenzio@unicatt.it

CREMIT, Research Centre on Media, Information and Technology Education, Department of Education

Catholic University of Milan, Assistant Professor

Email: simona.ferrari@unicatt.it

CREMIT, Research Centre on Media, Information and Technology Education, Department of Education

Catholic University of Milan, PhD Student

Email: lorenzo.decani@unicatt.it

CREMIT, Research Centre on Media, Information and Technology Education, Department of Education

Catholic University of Milan, PhD Student

Email: sara.lojacono@unicatt.it

CREMIT, Research Centre on Media, Information and Technology Education, Department of Education

Catholic University of Milan, Full Professor

Email: piercesare.rivoltella@unicatt.it

In recent years, social media have become a mirror for many adolescents: young people experiment online, testing their own limits and possibilities, and they build their identity day by day (Boyd, 2014). The consequences of this new behaviour are important and include sexting (Temple, 2012, 2014), self-exposure, self-objectification and identity manipulation. Many of these behaviours pass through the media themselves, as they work as a sort of megaphone or extensive sharing platform.

This paper aims to reach two goals. The first is to share a new perspective with educators and researchers named Peer&Media Education (Ottolini & Rivoltella, 2014)—a model developed in recent years to reach young people and foster their “awareness” of media and their health (Ottolini & Rivoltella, 2014). The result is a new methodological framework fostering the responsible use of social media and digital tools and also helping young people to keep healthy habits. We will present the framework in sections1 and 2.

The second goal is to discuss the results of the research Image.ME, run by Cremit, which studied the uses of social network sites, their impact on relationships and identity and the incidence of risky behaviours. In fact, the research is built according to the Peer&Media Education perspective, preventing risky behaviours and supporting media awareness. We will discuss this in section3.

Keywords: Media Education, Peer Education, Peer&Media Education, digital media, sexting, identity, body, social network, prevention

Media Education (ME) and Peer Education (PE) are both facing a new era after several decades from their establishment in the field of education. Starting from these changes, and the definition of a new perspective (Peer&Media Education), this paper tries to define a new idea of how to prevent/promote prevention/promotion of good habits, working with and on the media, in order to deal with the emerging needs expressed by adolescents and adults, as described in the research Image.ME run within this new theoretical framework. What follows is an attempt to discuss the methodology of Peer&Media Education—after a short presentation of its origin and the reason why ME and PE need to walk together—describing the research on the phenomenon of sexting (sex + “texting”), which means the exchange of explicit contents, texts, images and videos of a sexual nature through digital media.

When, in 1973, the Conseil International du Cinéma et de la Télévision defined Media Education (ME) as “the study, teaching and learning of modern means of communication and expression considered as specific and autonomous discipline in the theory and pedagogical practice,”[i] certainly no one could imagine the limitations of this short definition.

To study the media is still important, especially to understand their evolution; however, it cannot consist only of media analyses, as we will see. In 1973, miniaturized, cheap cameras and editing programs did not exist, especially accessible to all (even to children aged 6!) and media certainly did not represent “partners” in our everyday life.

The evolution of Media Education can be briefly defined as an effort to “extend the boundaries”—it does not occur only at school, as it usually happened in the past (Rivoltella, 2001), and it is not just a specific theme for media educators. ME seems to be part of education in a broader sense, as Geneviève Jaquinot-Dealunay stated some years ago: ME is simply education (Jaquinot-Dealunay, 2008); it is a mix of “to do” and “to reflect”. It is an act of citizenship (Rivoltella, Bricchetto, & Fiore, 2012).

Referring to the second theoretical perspective, Peer Education is now facing a time of growth, along with new challenge and new risks, similar to ME.Compared to traditional interventions, aimed to “warn against something”—substances, risks or discomforts—working with PE does not mean providing contents or technical knowledge, but rather providing new intellectual tools for analysis and reflection, forgetting “indoctrination” for promoting critical thinking (Croce & Gnemmi, 2003). This idea has been developed over the last few years, at least in the Italian debate, and the outcome has been recently presented to educators, teachers, medical staff and health workers in the public sector (Ottolini & Rivoltella, 2014).

We cannot forget that, from its beginnings, ME and PE Media Education and Peer Education (even separately) have always worked on actual problems, facing contemporary issues, helping people to live actively and supporting a critical reflection on current practices and emerging habits related to media, identity, body, relationships, friendships and self-expression. That is why Peer&Media Education is a perfect framework for working with behaviours, for example dealing with sexting, as we will describe.

Such practices are spreading among tweens and teenagers. In Italy, sexting was first detected in 2010, thanks to The National Observatory for Children and Adolescents. In 2012, the Commission focused on the "sexting" phenomenon, seeing an increasing number of children and young people posting their pictures on the Internet in skimpy outfits and other such provocative behaviours.

This concern is also explicit in the Official Journal of the European Union (15 November 2012), in which sexting is mentioned among the risks linked to the Internet, in particular for "the majority of young people who have received no prior training on the intelligent and responsible use of the intelligent and responsible social networks".

Despite these indications, there are no specific studies on this topic in Italy.

For a first indication, we have to look at the American research context, in particular the study "Teens and Sexting", by the Pew Research Center's Internet & American Life,[ii] investigating cell phone use as a tool for sexting.

In Europe, we can quote the EU Kids Online[iii] research, conducted in 25 European countries, which documents the risks associated with sending and receiving sexual online messages or images. According to the data, 15% of youngsters involved in the research—aged between 11 and 16 years—received messages or pictures of a sexual nature from peers, and 3% reported to have sent or posted online messages of this type. Among those who have received such messages, nearly a 25% stated having been annoyed. Half of the latter also reported to having been fairly or very upset, and 38% of European children in this situation deleted the unwanted messages and/or blocked the person who sent those (36%).

Regarding parents, 41% of those whose children claim to have seen sexual images deny this possibility. Parents therefore are not aware that their children look at pornographic images online, and very often they are totally unaware of the fact that their children have been victims of online offenses. The tendency is to label this phenomenon as a natural consequence of the massive use of digital media, a result of a plot between the media environment and social practices. This simplistic idea, not supported by research, seems to free adults from their responsibility and educational role, creating a highly dangerous attitude.

There are two ways in which Peer Education and Media Education meet. We will discuss of these briefly in an attempt to depict a clear image of their theoretical framework.

The first is about their aim, which is critical thinking. What PE has always done is to train youngsters so they can help other youngsters to become aware of the risks of sex and drugs, as stated in the previous paragraph. If you “think with your head”, you’re able to understand that if you don’t use condoms, it’s possible that you could get a disease, and it is the same thing with drugs and alcohol addiction (Carenzio, Gnemmi, Ferrari, & Rivoltella, 2015). Critical thinking frees us from what people or friends mainly argue: When we consider the effects of our actions, we’re able to see them and choose what is best for us. And this is more effective if youngsters work in a reciprocal way, without adult intervention but rather through peer training: Teaching them to become “peer educators” means enabling them to help their friends to become aware, too (this is the basic notion behind PE).

In addition, Media Education traditionally aims at critical thinking. In the past this meant being aware of media messages in terms of identity development and models. Media have always been considered as tools that are able to impact our behaviours and values. So it is quite different to receive messages passively versus in an active and critical way: In the first case, we will be probably influenced; in the second, we have the chance to “appropriate” tLambrate_2014 2015_Selfie_ok_01.avihe messages, filtering them and evaluating what is good or not.

In both cases, we have two methodologies and perspectives with the same pedagogical meaning: to make youngsters aware and thus enable them to think critically.

The second way of convergence relates to becoming part of the same pedagogical framework and is represented by digital and social media development and facing a real change between old and new media. The old forms—first of all television—had an impact basically through their contents. The problem with radio and TV was that, being “mass” media, they were considered able to produce a unique way of thinking in their audiences (Martin Barbero, 2002; Masterman, 1990). From a pedagogical point of view, the solution was to make people able to understand and deconstruct media messages. For many years, Media Education consisted of teaching youngsters how they could analyse the media; the idea was that deconstructing messages could provide a way to get beyond what was presented and reveal the “dark side” of the media (Buckingham, 2003; Rivoltella, 2001, 2005).

Nowadays, the problem with digital and social media is not only about contents, but rather mainly about media themselves. Online gambling, online pornography and video gaming are some of the activities that lead to concern for the youngsters in our society.

In these cases, the problem does not relate to contents (bad or good, true or false), but rather to behaviours that media can promote in youngsters. This is the case of “addiction without substances”, a common case of addiction in our society—thus, critical thinking doesn’t merely concern contents.

This idea explains the connection between Peer and Media Education (Ottolini & Rivoltella, 2014). PE considers media simply as tools for prevention: For example, if the aim is to encourage youngsters to use condoms, we can organise a group to produce a TV spot about this issue. Youngsters use media as an opportunity to reflect on their sexuality or sexual expectations. In the case of Peer Education, media become tools, similar to the instrumental idea behind Media Education (Masterman, 1990): This means educating with the media.

In the case of gambling, sexting and other examples of digital behaviours, media are both tools and problems. We cannot use them only as tools for prevention, because they are simultaneously what we have to protect youngsters from.

Peer Education isn’t enough. We need more media competencies, and these could be effectively provided by Media Education.

Finally what we get is a new educative perspective—Peer&Media Education—whose profile can be defined in two ways.

The first refers to the mutual articulation of the two terms “media” and “peer”. Accordingly, Peer&Media Education can mean the following:

1) Educating peers with the media—This is the case of the use of video in Peer&Media Education activities. We can think of video making or video analysis, activities aimed to help youngsters think about their practices and develop critical thinking. In Italy, the first steps of PE took place around 1996, as described by Emilio Ghittoni, spreading from school to school as a sort of positive virus (Ottolini & Ghittoni, 2011) as discussing HIV with adolescents is an important theme dating back to that time. On the other hand, Peer&Video Education started around 2008, developing a new idea of PE with videos to promote and develop positive habits among adolescents (Ottolini & Rivoltella, 2014).

2) Educating about the media with peers—This is a case of group work. As we have already said, prevention is more effective if the educators are not adults: When youngsters work in groups, they have a chance to reflect together, feeling freer to express their ideas than with teachers or animators leading the setting (Croce & Gnemmi, 2003).

3) Educating peers about the media—When planning an activity to prevent sexting, we must train peers both about sex behaviours and digital media features. Peers will act in groups of youngsters whose aims will be: a) preventing sex addiction, an inappropriate relationship with one’s body and cyberbullying episodes and b) developing an appropriate way of using digital media (critical and responsible).

The second way in which we can understand the relationship between the concepts of “peer” and “media” relates to three basic situations (Ottolini & Rivoltella, 2014), as follows:

1) Brick Peer&Media. This is the case of Peer Education 1.0. Trainers meet peers at school (face-to-face; this is where the term “brick” comes in), where through teacher mediation, peers use the media in their activities, but mainly as tools, without planning any online activities.

2) Brick&click Peer&Media. In this situation, peers meet at school and work face-to-face, but they start to use digital environments to communicate and share ideas (a “click situation” is made of online activities). These environments are open, and they can allow youngsters to meet other people outside school, talking with them about prevention or similar issues.

3) Click Peer&Media. This is the case of Peer Education 2.0. Peers operate directly on social network sites. They enter youngsters’ communities, talk with them, try to be helpful in addressing different problems such as online sex, gambling, cyberbullying, sexting etc. This means that social networks are considered to be analogous with the streets or squares: This actually represents an important change for policy makers regarding prevention issues, as they are normally used to waiting for youngsters to go to hospitals or visit their offices. Now, as we can easily understand, they are forced to meet them in their own social/meeting places on the Internet.

Theoretically speaking, this shift started—at least in Italy—in 2011, defining PE 2.0 as “a strategy of prevention close to the education of a real citizenship (as digital citizenship) as stated by Media Education, as a necessary answer to the social, technological and identity changes in peer groups”.[iv]

3.1 Context, beneficiaries, aims

Image.Me—Bodies, consumption and transformation of youngsters in the social media mirror—is a biennial action research project (June 2013–June 2015) funded by “minor landmark grants”[v] of Fondazione Cariplo.[vi]

These special grants finance initiatives promoted by non-profit organisations, delivering actions with a significant philanthropic value and of an adequate size, to be highly impactful on life quality and on the cultural, economic and social development of the local community involved.

The project was designed in order to study and prevent teen sexting and was developed as a partnership between CREMIT,[vii] Spazio Giovani[viii] and Industria Scenica,[ix] with the support of the Provincial Office of the Ministry of Education and the Local Health Authority Service (ASL) whose mission is to protect and promote health and healthy lifestyles for all people, in particular the youth.

The direct beneficiaries of the project were high school students, while indirect beneficiaries of the project were parents, teachers and social educators living in Monza-Brianza (in the metropolitan area of Milan, with 55 municipalities). The high school population (14–18) in the 2013/2014 school year was made up of 28,341 students in 561 classes. Public high schools are located in 12 municipalities.

The main aims of the research can be summed up as follows:

- to define the phenomenon of sexting;

- to promote better knowledge of sexting, helping adolescents to deal with it properly with empowering tools;

- to work with adolescents in order to prevent sexting, using Peer&Media Education as the main framework and

- to train and inform adults (parents and health professionals), in order to make them more responsible and informed about digital media, identity and social practices (not just sexting).

3.2 Methodology and tools

As is common in action research, Image.ME is more of a holistic approach to problem solving, rather than a single investigation method. It “aims to contribute both to the practical concerns of people in an immediate problematic situation and to further the goals of social science simultaneously. Thus, there is a dual commitment in action research to study a system and concurrently to collaborate with members of the system in changing it in what is together regarded as a desirable direction. Accomplishing this twin goal requires the active collaboration of researcher and client, and thus it stresses the importance of co-learning as a primary aspect of the research process” (Gilmor et al., 1986).[x]

What is peculiar in this case is the Peer&Media Education framework as adopted to address sexting, with some differences, that we sum up here:

- the connection between formal and informal contexts to collect and discuss data (in school, outside of school);

- the use of active empowering methodologies and

- the use of social media, such as Facebook, as a new space to work in and as content to reflect on.

3.2.1 Literature review and questionnaires

In its initial phase, the research aimed to build a “knowledge map” of sexting through a national and international literature review, in order to highlight the extent of the phenomenon and study the survey instruments used in previous research.

This made it possible to create three questionnaires, with an educational “soul” and a scientific background, aimed to reach adolescents, parents and health professionals from local health services (our three main targets).

We collected 889 questionnaires from 20 secondary schools, reaching 45 classes. The participants were 49.7% males and 50.3% females: 29% from the first class (13–14 years old), 22% from the second class, 20% from the third, and 17.7% and 11.3% from the fourth and fifth classes, respectively.

The data collected through questionnaires were gathered and input into a research-specific online software.[xi] This allowed an initial overall view of the key aspects to focus on, based on descriptive statistical measures. Then, by exploiting its embedded tools, the researchers were able to draw correlations between the most interesting variables (Pisati, 2003).

This further step could not be applied to the Facebook quiz due to the lack of a structured frame (questions were not posted as a whole set) and also to the very purpose of this tool, which of course was intended to collect answers free from parental or teachers control and also to prompt engagement in the active phases of the research.

In the main questionnaires, however, the core questions aimed to analyse the use of digital media in everyday life (especially mobile phones and social networking sites), the effective knowledge and ideas on sexting, adolescents’ experience with sexting and the link between social media, identity performance and identity building.

As for the analysis of data coming from sources other than questionnaires (selfies, Facebook posts and other miscellanea), it was carried out following a qualitative approach, which is best suited for such an aim (Cardano, 2003).

3.2.2 Seminars and training sessions

The results of the questionnaires[xii] have been delivered during three seminars and have become the new background through which training sessions with adolescents, parents and health professionals have been organised, using Peer&Media Education techniques (video making, group analyses, peer education).

The aim, with adolescents, was to discuss the topic of sexting to build knowledge and tips on how to deal with it and make videos to address peers’ interest and public awareness on sexting. With parents, the main aim was to help them to deal with sexting and learn new pedagogical issues around digital media and digital citizenship. All videos are on YouTube.[xiii]

With health professionals, the aim was to discuss the new working “arena” where they can meet, reach and help young people, as prevention no longer takes place in hospitals and caring and counselling services (see Peer&Media Education 2.0).

3.2.3 #respectyourcyberself

To meet formal and informal contexts and to provide a common framework for every single action (as integrated and linked one to each other), Image.ME designed an original campaign—called #respectyourcyberself—based on the study and creation of a recognisable mascot to meet the research target (the character Ops, a very large-eyed puppet, see Figure 1) and organised several social events to disseminate awareness on sexting in different scenarios: markets, streets, schools, conferences, scientific events, shows, public places and discotheques.

Figure 1: Ops, the mascot of the research project

The campaign has been supported by the active use of a Facebook page,[xiv] a website (www.imageme.it),[xv] stickers, the mascot Ops and a video clip of an original song written by locally known rappers (Scarty e Tempo, “Respect your cyberself”).

3.2.4 Social media as tools and scenario

As said before, Image.ME is intended to connect formal and informal spaces and education, including two more actions: a quiz on Facebook and a small-scale work on selfies (as a very common way to depict identity and bodies via digital media) during informal social events, both based on data collected during the research.

The idea of using a Facebook quiz is interesting for educational purposes, as it can help raise awareness among a community or allow the community to express its point of view and take a stand. As the topic was somewhat of a touchy subject, many interesting aspects were not addressed in the form of a questionnaire (delivered at school), but rather took place on Facebook as a common ground for adolescents.

The work with selfies (as format and content) meant not only to share opinions on how youngsters define body and beauty status, but also on how they deliver identity and build it with mash-ups, memes, colour editing etc.[xvi]

The research staff is now facing the complex analysis of all the products collected (videos, screenplays, posters, brainstorming ideas, slogans). The results will be a good starting point for future projects and a firm basis for further research in the same subject area.

3.3 From data to ideas to work with adolescents

The literature argues the need for educating young people about the consequences of sexting (Muscari, 2009; Brown, Keller, & Stern, 2009). We have tried to do it, using the Peer&Media Education model, both to research and to create interventions with adolescents.

We started with the idea that understanding sexting from the perspective of teens is fundamental to developing strategies for preventing potential harm (Heath et al., 2009).

The insights from the first quantitative study (questionnaires) have been used to discuss with peers so they can design their work in schools and on Facebook (using the quiz function) to support online reflection.

3.3.1 Searching for a definition

What we immediately identified was the lack of a definition of sexting, and not only among teens. In actuality, it is a sort of an umbrella-term that covers different definitions and behaviours. Eighty per cent of Facebook respondents consider sexting as “sending and receiving sexually explicit images via mobile phones”, and 13,3% say it is just “to take a photo in a sexy pose”.

Other recent studies havehighlighted this multifaceted phenomenon (Saleh et al., 2014):

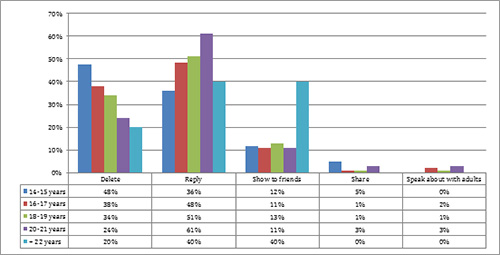

Figure 2: Reaction to a sexually explicit messages or images by age distribution

Nowadays there is a variety of contents included under the term “sexting” (Livingstone et al., 2011). As young people are growing up in an increasingly sexualised world driven by technology (McGrath, 2009), we need to consider the phenomenon and allow teens to become co-researchers in order to reflect on behaviours and contexts and to help them to be able to critically receive media discourses about sexting.

To reach this goal, we needed a different methodological approach and a new investigative direction: We found it in Peer&Media Education.

3.3.2 Peer work in the classroom

We trained peers to manage focus group sessions in the classrooms. Then they managed a brainstorming session around the idea of sexting (to get their representations of it) and reflect on the causes and effects using video-cases (for example, an Amanda Todd video).[xvii]

Facing with peers allowed the youngsters to freely express their representations of media and personal behaviours.

The collection of representations allowed us to reach two main goals (Ferrari, 2009):

- to leave a deterministic idea about media and behaviour (for example, the idea that social media fostersexting) and

- to consider users in terms of their personal needs, skills, knowledge and performances as the starting point of educational intervention.[xviii]

Commenting on why teens might engage in these behaviours has led peers to distinguish between “aggravated or experimental cases”[xix]of sexting (Wolak, Finkelhor, & Mitchell, 2012).

According to the questionnaires and Facebook quiz, sexting is conducted and experienced particularly to have fun (20%), to impress or gain attention (12,6%), to be popular, (11,6%) and to engage couple relationships or flirting (10,2%). This behaviour is not focused on harming or harassing individuals.

Peers, supported by media educators, fostered the intervention, reflecting on what to do if they lose control by means of a “joke”.

The viral spread of these images and the associated shame reportedly leads to social, psychological and legal consequences for victims (Katzman, 2010).

Students and peers became authors of suggestive prevention messages at different levels due to the process in which they were involved, such as videos and texts.

3.3.3 Mixed methodology for deeper results

As already stated in discussing the methodology, school-based surveys have some limitations in terms of the questions allowed. From the data collected in the first phase, the research team decided to analyse possible correlations of sexting with gender (Davidson, 2014), age (Mitchell et al., 2012) and sharing practices using mixed methods to reach deeper results.

Gender differences exist in term of underlying motivations, social conditions and attitudes toward the behaviour. Girls are significantly more likely than boys to be bothered by receiving sexting images, and they mainly felt embarrassed(female 39% vs. male 9%). Twenty-two per cent of females confirmed receiving messages from unknown people (1.9% of males). But girls seem more open to sharing Facebook pages than boys and pay special attention to their looks (70% versus 50%) in taking a selfie. Moreover, they use artistic photos to represent themselves on Facebook.

The literature points out the risks of coercive gender, discussing as sexting as an adult dynamics toward female teens (Temple et al., 2012).

Referring to age, emotions dealing with sexting among youngsters are significantly different from those of older individuals: that is embarrassment versus fun, respectively.

Sharing has a social connotation in adolescence. It “may often occur within the limit of one-to one relationships, forwarding and sharing implicitly involves one or more third parties and may typically occur without the concern or knowledge of the image’s original sender. This not only suggests a nexus between sexting and bullying behaviour but also feeds into potential legal issues surrounding the distribution of illegal pornographic material” (Saleh et al., 2014, p. 266). So, we connect this with the intimacy implied in relationships.

There is a different connotation of an image sent between partners, between partners and shared with others or between young people where at least one person hopes to be in a relationship with the other. The exchange of sexting among partners is considered a common behaviour among adults (83.2%) and less so among teens (16%).

From the focus group to the analysis of the selfies, it is clear that images of young women are reportedly being distributed without their consent, but they all with pictures taken without forcing them. The protagonists had not thought about the effect of images “gifted” to the Internet. The participants (aged 16–21) also argued that if someone doesn’t think before taking a photo or posting it, that individual is guilty and responsible for that act.

This (as other data showed) points out how pictures and images are the strongest tools to represent identity and states of mind among adolescents and that we all need to become aware of the risks of this practice.

Even in this situation, the research confirmed that adults are not included when something bad happens online or when sex-related contents are delivered or received.

At the end of this paper we will present three highlights from our research, which can suggest new strategies for healthcare and education and open new directions for research and experimentation.

First of all, it is clear that nowadays media are no longer simply tools available at the edges of our social lives. On the contrary, they are the skin of our culture (de Kerkhove, 1990): They are what makes possible our knowledge of things, our representation of reality and our relations with other people. Our research aimed at discovering how youngsters use the media for body and self-representation, for expressing themselves and their sexuality and for building up and breaking apart their relationships. It is a chance for freedom but also a risk. Viewed in this way, media really become the new space into which each of us is called to be a citizen: Media Education is no longer something we can choose to accept or not; it is the core part of our lives.

This new idea of the media, and of their social presence, asks scholars and educators to imagine new methodologies of research and strategies of intervention. This is the case with Peer&Media Education and the use of social media and social animation. As we saw in this paper, Peer&Media Education is a new opportunity both for health operators and for educators: It views the media simultaneously as tools and spaces for peering and as an issue about which we have to take care for prevention and education. On the other hand, our research showed how Facebook can be used as a focus-group space, or how to use drama (as in the case of the puppet Ops and of its performances outside discotheques) for elaborating youngsters’ representations and ideas. Research in the field of educational sciences has to provide solutions and not simply put youngsters under the lens of its microscope.

Finally, Peer&Media Education leads Media Education out of the school and allows for it to meet youngsters in their real-life environments. This means that critical thinking—really the main issue in the case of Media Education—can be extended to everyday life and behaviours.

Boyd, D. (2014). It's complicated: The social lives of networked teens. New Haven, London: Yale University Press.

Brown, J., Keller, S., & Stern, S. (2009). Sex, sexuality, sexting, and sexed. Adolescents and the media. The Prevention Researcher, 16(4), 12-13.

Buckingham, D. (2003). Media education. Literacy, learning and contemporary culture. London, New York: Polity Press.

Cardano, M. (2003). Tecniche di ricerca qualitativa. Roma: Carocci

Carenzio, A., Gnemmi, A., Ferrari, S., & Rivoltella, P. C. (2015). Peer & Media Education: un nuovo spazio di intervento media educativo in ottica transmediale. In A. Garavaglia (Ed.), Transmedia education. Contenuti, significati, valori. Milano: Unicopli.

Croce, M., & Gnemmi, A. (2003). Peer education, adolescenti protagonisti nella prevenzione. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Davidson, J. (2014). Sexting. Gender and teens. Rotterdam: Sense Publishing.

de Kerkhove, D. (1997). The skin of the culture. Investigating the new electronic reality. Philadelphia: Kogan Page Ltd.

Ferrari, S. (2009). Instruments to collect media representations.Paper at Media Literacy and the Appropriation of Internet by Young People, Faro 16-18 February 2009.

Gilmore, T., Krantz, J., & Ramirez, R. (1986). Action based modes of inquiry and the host-researcher relationship. Consultation, 5(3).

Heath, S., Brooks, R., Cleaver, E., & Ireland, E. (2009). An introduction in researching young people’s lives. London: Sage Publications.

Jaquinot-Delaunay, G. (2008). MediaEducation: quand il n’est plus temps d’attendre...

Media education: When the waiting is over. In U. Carlsson, S. Tayie, G. Jacquinot-Delaunay, & J. M. Pérez Tornero (Eds.), Empowerment through media education. An intercultural dialogue (p.59-66). Göteborg: Nordicom.

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence Culture: where old and new media collide. New York: New York University Press.

Martin Barbero, J. (2002). El oficio de cartógrafo. Traversias latinoamericanas de la comunicación en la cultura. Santiago del Chile: FCE.

Mascheroni, G. (2012). I ragazzi e la rete: la ricerca Eu Kids online e il caso Italia. Brescia: La Scuola.

Masterman, L. (1990). Teaching the media. London: Routledge.

McGrath, H. (2009). Young people and technology. A review of the current literature. Melbourne: The Alannah & Madeline Foundation.

Mitchell, K. J., Finkelhor, D., Jones, L. M., & Wolak J. (2012). Prevalence and characteristics of youth sexting: A national study. Pediatrics, 129(1), 13-20.

Muscari, M. (2009). Sexting: New technology, old problem, Medscape. Public Health & Prevention, May.

Ottolini, G., & Rivoltella, P. C. (Eds.) (2014). Il tunnel e il kajak. Teoria e metodo della Peer&Media Education. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Pavlic, B. (1987). UNESCO and Media Education. Educational Media International, 24.

Pisati, M. (2003).L'analisi dei dati. Tecniche quantitative per le scienze sociali. Bologna: Il Mulino

Rivoltella, P. C. (2001). Media Education. Roma: Carocci

Rivoltella, P. C. (2005). Media Education. Fondamenti didattici e prospettive di ricerca. Brescia: La Scuola.

Rivoltella, P. C. (2013). Educare (al)la cittadinanza digitale. Rivista di Scienze dell’Educazione, 51(2), 214-224.

Rivoltella, P. C., Bricchetto, E., & Fiore, F. (2012). Media, storia e cittadinanza. Brescia: La Scuola.

Temple, J. R., Paul, J. A., van den Berg, P., Le, V. D., McElhany, A., & Temple, B. W. (2012). Teen sexting and its association with sexual behaviors. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 166(9), 828-833.

Saleh, F. M., Grudzinska, A., & Judge, A. (2014). Adolescent sexual behavior in the digital age. Consideration for clinicians, legal professionals and educators. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wallace, P. (2000). La psicologia d Internet. Milano: Raffaello Cortina.

[i] Pavlic, B., (1987). UNESCO and Media Education, Educational Media International, 24, 32. A few years later, the same CICT proposed a broader definition that sees Media Education as a viable path "at all levels: primary, secondary, post-secondary, adult education and continuing education and in all circumstances", expanding the place occupied by the media, no longer conceived only as " practical arts and techniques".

[ii] See “Sexting: New study & the ‘Truth or Dare’ scenario". URL: http://www.netfamilynews.org/?p=28684

[iii]http://www.lse.ac.uk/media%40lse/research/EUKidsOnline/Home.aspx.

[iv]Ghittoni, E., & Ottolini, G. (2011).Un seminario che apre al futuro, in G. Ottolini, (Ed.), Verso una Peer Education 2.0? (p. 6). Animazione Sociale, 251.

[v]Since its establishment in 1991, this foundation aims at operating on the basis of the principle of subsidiarity, anticipating needs and fulfilling its special mission of being a resource that helps social and civil organizations better serve their community. Seehttp://www.fondazionecariplo.it/en/grants/major-landmark-grants/minor-landmark-grants.html.

[vi]http://www.fondazionecariplo.it/en/the-foundation/la-fondazione.html

[vii]CREMIT is the Research Centre on Education about Media, Information and Technology based at the Catholic University of Milan. The main activities developed by CREMIT can be summed up in five nodes: school support concerning research, training and educational actions in the media field; research activities in the field of Media Education and Information Literacy; Development and analysis of products and didactical tools (kits, guidelines etc.); implementation of educational projects in the field of Media Education; and seminars, meetings and conferences dedicated to media and technology education. Web site: http://www.cremit.it.

[viii]Spazio Giovani was established in Italy in 1994 as a non-profit company, active in the field of youth work, supporting and empowering young people in their growth and personal development, their parents/teachers/educators inside local communities to make them acknowledge youth as a local resource (and not as a social problem) and support their growth with positive approaches.

Web site:http://www.spaziogiovani.it/cms/.

[ix]Industria Scenica is a cultural non-profit organization that enhances the creative act of individuals and communities through social performance in order to generate development and cohesion, to promote economic growth and cultural innovation and cultivate a specific territorial identity. Web site:http://www.industriascenica.com

[x] Gilmore, T., Krantz, J., & Ramirez, R. (1986). Action based modes of inquiry and the host-researcher relationship, Consultation, 5(3), 161.

[xi]Http://www.questionpro.com/

[xii] We have collected 99 questionnaires from parents and 100 from employees working in health and prevention.

[xiii] Videos are collected on the Youtube channel of Industria Scenica, one of the research partners involved in video making sessions with adolescents and parents: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCcGZI-JJqfZDNevRiyg_7Mw

[xiv]https://www.facebook.com/progettoImageME?fref=ts.

[xv]4,235 visits, 54,254 pages viewed.

[xvi] We have worked on 146 selfies.

[xvii]We have worked with four groups of peers during seven sessions for a total amount of 15 hours of work for each group. Peers then visited 45 classrooms (distributed in four schools) during two sessions.

[xviii]Representations can predict subjective media use, relationship and functions supported.

Analysing the performances would then bring out personal connotations given to the media (in terms of personal development, social development, personal discomfort), the emotional side (positive, negative, ambivalent) and main expectations.

Reflecting together on motivations helps to take into account “the manner in which the behaviors are commonly framed by in the context of media reports, policy discourse and research” (Saleh et al., 2014, p. 265).

[xix] The first includes cases involving adults with the explicit intent to harm, needing immediate police involvement, and the second deals with the majority of the situations studied, starting with sharing a sexual explicit message based on fun.